Jenny Holzer: Word Perfect

This American artist has been crafting her alphabetic art for 40 years. With seven recent solo exhibitions and unveilings, plus more to come, she could not be more relevant

Before there was Twitter, there was Jenny Holzer. Her text-based art, equal parts sardonic observation and angry political commentary, punches you in the mouth with a wry smile. And now, at the ripe age of 67, she’s having a moment – or, better, she’s prolonging her moment.

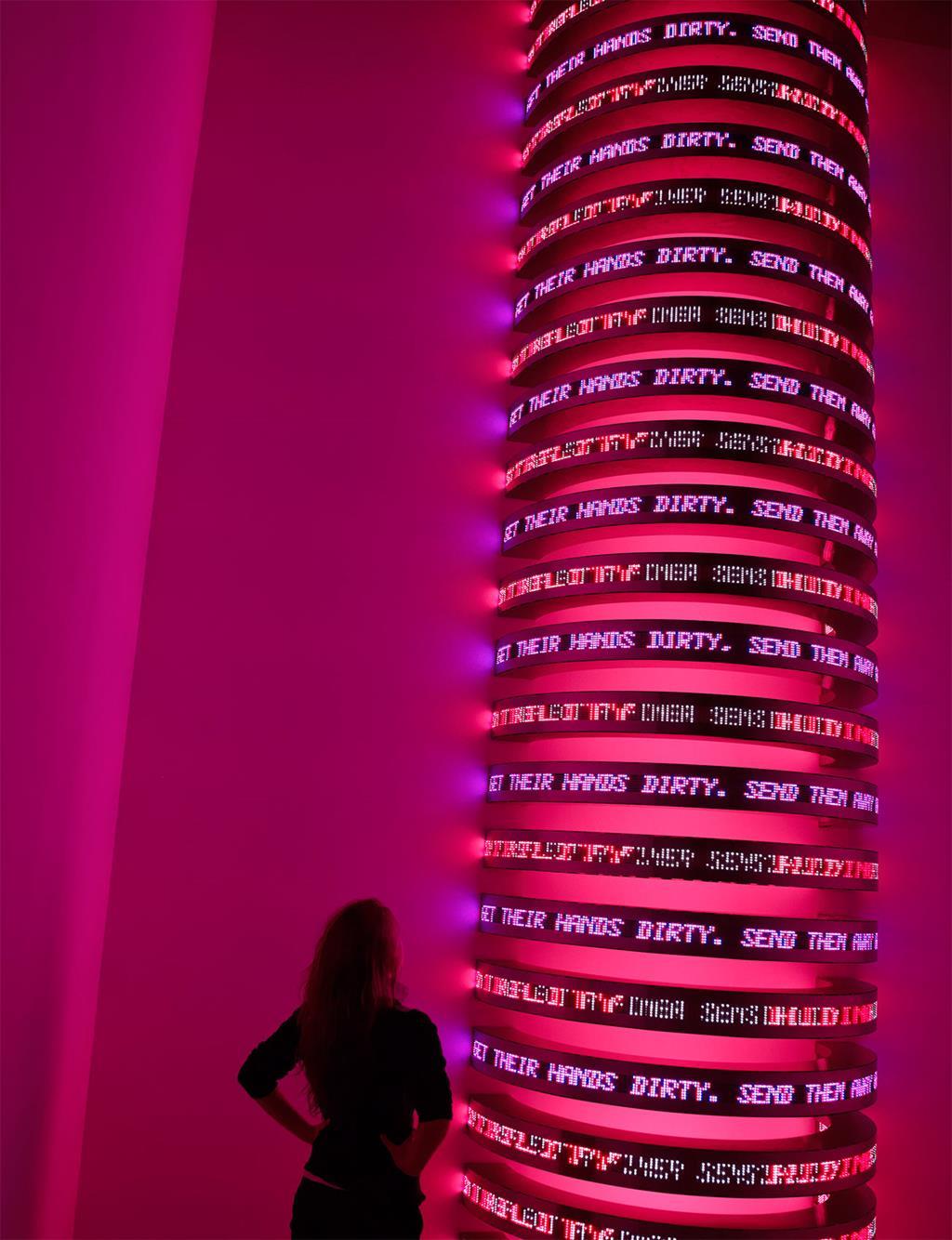

Holzer’s enigmatic work has been everywhere. In the late 1970s in New York City, she found her voice by anonymously posting cryptic aphorisms across Manhattan streets. Electronic text soon became her medium of choice, as in the deadpan Times Square billboard of 1982 that displayed the illuminated maxim, PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT.

Nearly all of Holzer’s work has this same plaintive, provocative tone. Like social media at its best, it is quick to grasp but reverberates more deeply. And Holzer achieves what social media cannot: perfect placement. It is hard to be more apt than her slogan painted on the side of the 1999 BMW V12 LMR concept car, the first and only BMW to win the 24 Hours of Le Mans race: THE UNATTAINABLE IS INVARIABLY ATTRACTIVE.

Recently, Holzer exhibited in New York, Berlin and Zurich, and last summer she worked with designer-du-jour Virgil Abloh on the catwalk show for his brand Off-White at the Pitti Palace in Florence, a city she also worked in 20 years ago with the fashion bad boy of the previous generation, Helmut Lang.

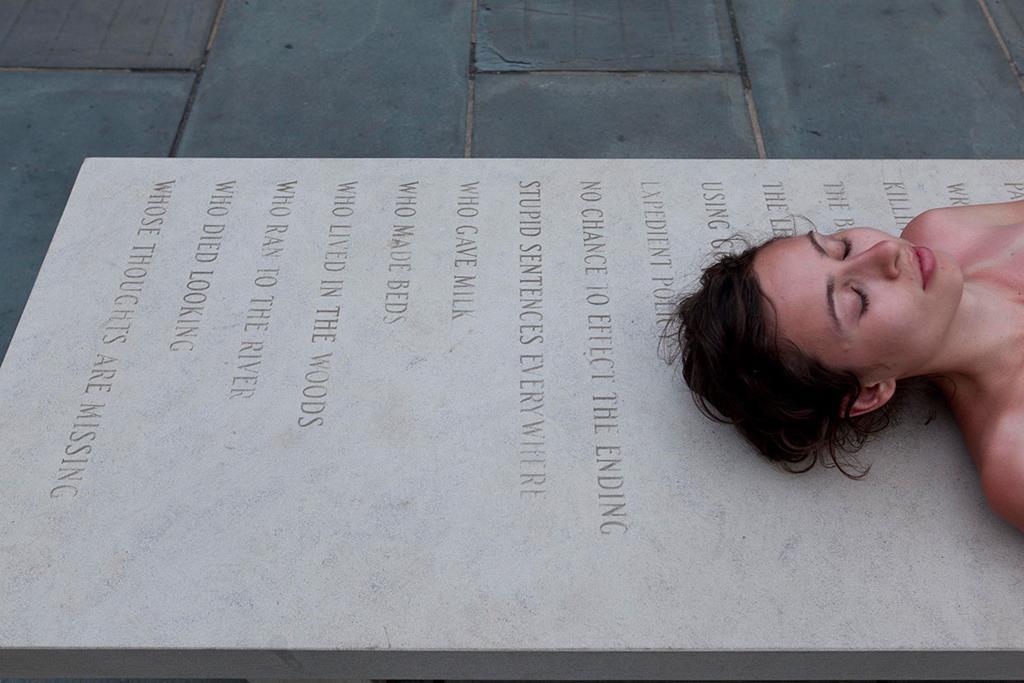

Memorial Bench II: Eye cut by flying glass…, 1996 (detail) © 1996 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY Photo: Erik Sumption

She also unveiled two major works, at the new US Embassy in London and at the new Louvre Abu Dhabi, both permanent, site-specific engravings in the walls.

But her most notable creation of last year – and the largest project of her career – happened at a much older site, Blenheim Palace blenheimpalace.com, one of Britain’s grandest country homes, protected by Unesco and set just outside Oxford. In previous years the palace has hosted Ai Weiwei and other globally renowned artists, but none has engaged with the surroundings in quite such an intimate way – and certainly not as critically.

Holzer says she was intrigued that the palace was “a prize for a victory in war”. (The palace was gifted to the Duke of Marlborough by Queen Anne in recognition of his triumph in the 1704 Battle of Blenheim.) For her exhibition, Holzer used the words of contemporary war survivors in a multitude of mediums to serve as stark reminders of the very human and unglamorous costs of warfare. “Rather than presuming to write about war,” Holzer told The Art Newspaper, “I thought I would leave it to someone who experienced it first hand.”

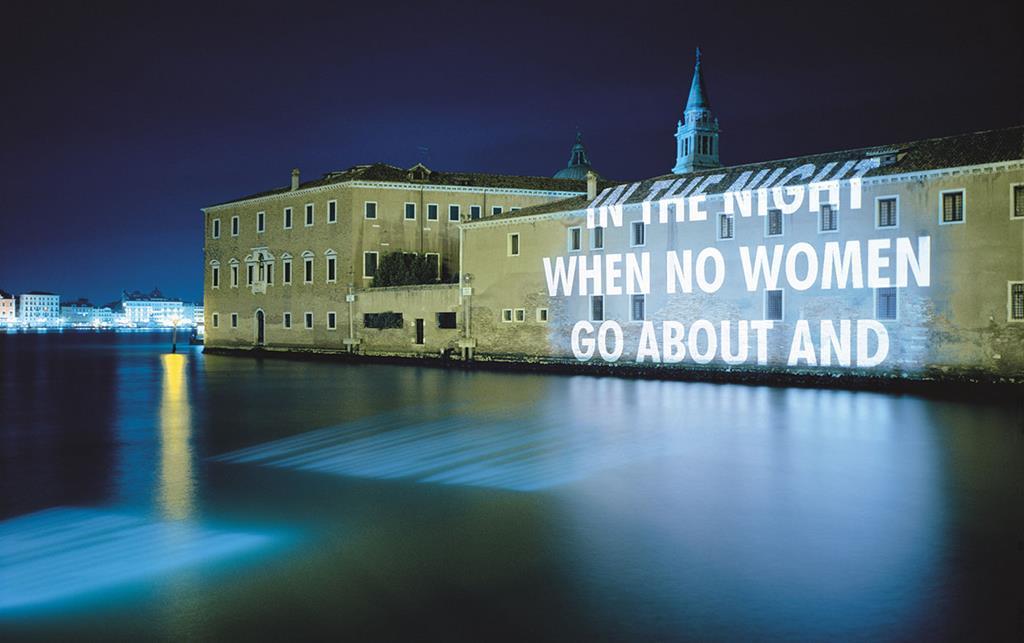

Xenon for Venice, 1999 © 1999 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY Photo: Attilio Maranzano

The tension that’s created between the sufferings and the spoils of war is Holzer’s speciality – and it’s more powerful than anything Twitter could achieve. However much social-media savvy her early works display, she needs no help from any platform: she has secured her position as the voice of the pain, the absurdity and the pathos of our modern age.

Black Garden, 1994 (detail) © 1994 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY Photo: Courtesy Städtische Galerie Nordhorn

Visit jennyholzer.com