Glass Roots Movement

From his dynamic gallery-cum-studio in London, Peter Layton and his team are shining a spotlight on the underappreciated art and time-honoured tradition of glassblowing

London is a city of contrasts in which the old and the new stand shoulder to shoulder. The Shard – the strikingly contemporary 72-storey skyscraper that towers over the capital – buzzes with the fast-paced energy of the modern metropolis. Yet just a short walk away, on charmingly historic Bermondsey Street, lies a quieter, more intimate space steadfastly devoted to preserving one of the world’s oldest art forms. This is London Glassblowing, a workshop and gallery founded in 1976 by Peter Layton, the master glass artist widely regarded as one of the founders of the British Studio Glass movement.

Now in his eighties, Layton is still guiding a dedicated team of skilled artists who keep the ancient craft alive, maintaining a unique hub of creativity where one can admire the best of contemporary British glass art. Since founding the studio nearly 50 years ago, he has sought to nurture budding talent and advocate for the magical discipline he first discovered during his academic years as a ceramist. “Having studied at the Central School of Art and Design in London [now known as Central Saint Martins] under some of the leading potters of the day, I was introduced to glassblowing while teaching ceramics in the US during the Swinging Sixties,” Layton recounts.

London Glassblowing (photo: Alick Cotterill)

London Glassblowing (photo: Alick Cotterill)

At the time, the Studio Glass movement, which viewed glass as an artistic material rather than one reserved for mass manufacture, was gaining momentum there. “I was attracted by the immediacy of the material, and the spontaneity and risk-taking required by the process.”

Layton’s first foray into glass was quite literally a baptism of fire. “I dropped a tool and picked it up just as molten glass rolled over the back of my hand. There was this wonderful smell of cooking meat,” he recalled in an interview with The Oldie magazine. Undeterred by his blistering initiation, he found himself at the forefront of an effort to bring the burgeoning stateside wave to the UK upon his return in 1968, fully committed to reviving and reimagining centuries-old techniques.

Peter Layton in the studio (photo: Alick Cotterill)

Peter Layton in the studio (photo: Alick Cotterill)

The endeavour proved to be an incredibly ambitious one. Not only were the costs associated with running a glassmaking workshop prohibitively high – such as the space, expensive tools and steep energy bills to power the furnaces – but the material was unpopular due to its translucent and reflective qualities. “In the late 1960s, there was little or no market for studio glass. I hawked my wares around the UK craft galleries, selling from the back of my car. There was considerable resistance to this new medium. Gallery owners were concerned about the need for special lighting.”

It soon became clear that London Glassblowing, originally established on the banks of the Thames in Rotherhithe, would need to rely on teamwork and collaboration to thrive. By joining forces with fellow glass artists – some of whom would work alongside him for many years – Layton was able to cultivate an ever-evolving group of creators that would support his vision for years to come, giving rise to a wealth of artistic expression and imaginative approaches in an often-underrated practice. “This is the issue that has been a major concern throughout my career,” he confesses. “Studio glass seems to be low in the hierarchy of media because, for centuries, glass has been a material for functional and disposable objects. Contemporary glass is still largely an undiscovered treasure and represents a golden opportunity for collectors and the public to discover and enjoy.”

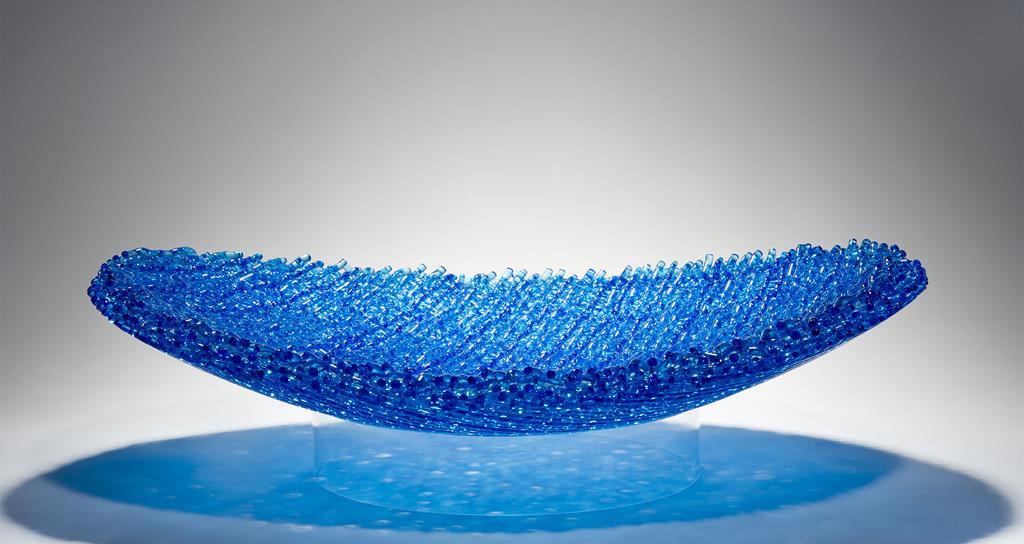

Duo of Blues by Nina Casson McGarva (photo: Sylvain Deleu)

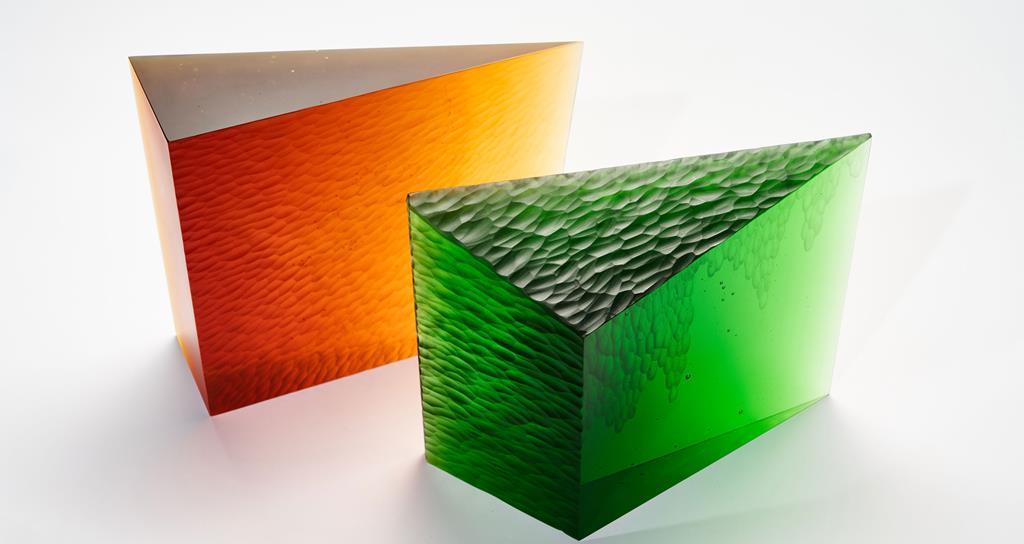

Salamis & Kara by Sila Yücel (photo: Alick Cotterill)

Dynamic Stance by Monette Larsen (photo: Valerie Bernardini)

Symbiosis by Laura McKinley (photo: Alick Cotterill)

Big Sur by Catheryn Shilling

Layton’s vision comes to life with striking vividness inside the space, which brims with works that challenge the limits of the form in diverse styles and techniques. Organic, nature-inspired shapes emerge from artists like Monette Larsen, Deborah Timperley and Nina Casson McGarva, while Tim Rawlinson, Harry Morgan and Sila Yücel explore geometric and architectural aesthetics. Others put a modern spin on traditional glassmaking methods: Laura McKinley employs the Italian incalmo method to seamlessly fuse two blown-glass elements into a single unit, while Cathryn Shilling utilises Venetian-style glass canes to create the fabric-like structures of her signature glass-cloth pieces. From David Patchen’s intricate kaleidoscopic patterns to the elaborate glass-enamel prints of Sophie Layton – Peter’s daughter – each creator pushes technical and visual boundaries in distinct ways.

“We look for exciting ideas and outstanding qualities across a range of concepts and technical inventions – artists who express the versatility and the magical qualities of the medium,” explains Peter Layton, whose own work is prominently featured in the gallery. His highly celebrated creations – held in collections across the UK, US and Europe, including London’s Victoria and Albert Museum – are distinguished by painterly swirls of vibrant colour, a testament to his decades-long dedication to mastering iridising, etching and creating opaque finishes.

Tim Rawlinson at work (photo: Alick Cotterill)

Tim Rawlinson at work (photo: Alick Cotterill)

“People are often gobsmacked when they enter our gallery. Their jaws drop in response to the vibrancy of our display – the huge range in colour and form of the pieces. Seeing the studio with its glowing furnace beyond the gallery provides a further level of excitement and fascination – the alchemy of transforming a molten material into a stunning object before their very eyes.”

Indeed, it is the open view of the artists dexterously wielding their tools in the glassblowing atelier, working together in near-choreographed fashion, that makes London Glassblowing so unique. Watching the process first-hand deepens visitors’ appreciation for the immense expertise and effort behind each creation. “It takes many years to master the art of glassblowing, and we are losing skilled glassblowers continuously. Handcrafting skills are endangered throughout the world. Sadly, in the UK, many university courses which cover glassmaking are closing in favour of tech.”

Sogetsu Arrangement and Roman Vase I by Sophie Layton (photo: Ailck Cotterill)

Sogetsu Arrangement and Roman Vase I by Sophie Layton (photo: Ailck Cotterill)

The art of free-blowing – where molten glass is shaped using a blowpipe and other tools – still relies on peer-to-peer learning. Coupled with rising energy expenses and soaring rents, the future of the craft appears uncertain. But Peter Layton is not one for giving up; instead, he encourages his team with the energy of an orchestral conductor: “We have faced many challenges in our efforts to create public awareness of this extraordinary medium, and we have survived many recessions when others have not. More recently, during the pandemic, we were able to switch quickly to selling online, which proved successful and kept us going throughout that tricky time.”

It is evident that, just as tradition and innovation have found a way to coexist in the city, the survival of this microcosm of creativity and talent requires both the preservation of its age-old techniques and a new generation of passionate glassblowers with fresh outlooks. While Layton and his team actively promote London Glassblowing at major public fairs such as Collect at Somerset House and PAD London, it is the community he built that he is banking on to ensure the workshop’s future: “We hope that my colleague Tim Rowlinson, together with my daughter, Sophie Layton, will continue to run the studio and gallery and continue to champion this extraordinary medium.”

Tim Rawlinson and Peter Layton in the gallery (photo: Alick Cotterill)

Tim Rawlinson and Peter Layton in the gallery (photo: Alick Cotterill)

Stay tuned for the upcoming collaboration between London Glassblowing and Centurion Magazine