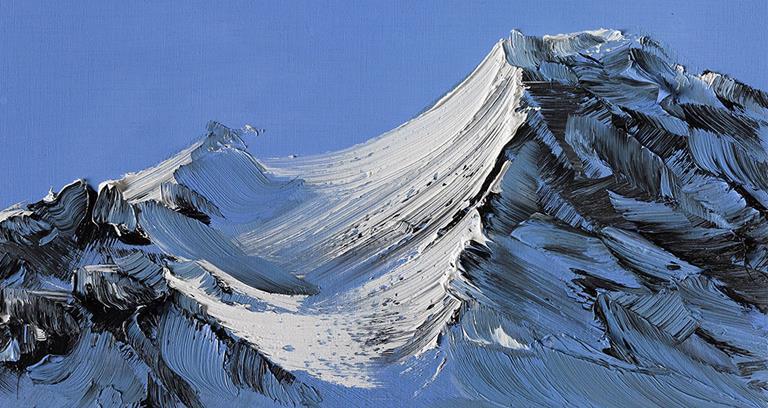

Conrad Jon Godly: Painting Light

This Swiss artist has led a remarkable life. We trace his creative path from celebrity photo shoots to paintings that are finding a devoted following in Japan

In Conrad Jon Godly’s first career, he spent each day trying to capture the impossible. Shooting for brands and publications across the globe for nearly two decades, his photographs hunted the ever-elusive glamour that defined the 1980s and 1990s. And then one day, after a particularly monotonous photo shoot in Milan, where he was then living, he was done.

The session didn’t go poorly – it was a cover for GQ that earned rave reviews – but Godly felt empty, bored by the process. The thrill of the chase was gone. And instead of swallowing the ennui and finding ways to manage, Godly did what only the bravest of us do: he walked away entirely.

Public acclaim and worldly success were not – and are not – his goals. He is more focused on realising the power of his subjects: churning with emotion and without clear antecedents, his paintings reach not towards the changeable glamour of the human world but towards the magnificent simplicity of the natural one.

In that way, Godly’s second career, that of a painter, is not so different from his first: he is still chasing the impossible. But for the Davos native, who grew up surrounded by the splendour of the Swiss Alps, he seems to have found his calling.

Spes 8 | Credit: Conrad Jon Godly

Godly’s break with photography was followed by a reacquaintance with painting in the mountains of eastern Switzerland. Isolating himself in a cavernous former textile mill, Godly says, “It took me four years of practice to finally produce pieces that I liked.” He had studied painting in Basel in the mid-1980s, turning to photography soon afterwards, after a long stay in San Francisco. His return to painting in 2004 drew very little from those early experimentations, he says with a sigh: “When I was young, I’m sad to say I liked the very trendy things in the art world. Now I’m seeing things with a different eye.”

There is a long history of Germanic painters who have tried to capture the majesty of the mountains, from the 19th-century Romantic Caspar David Friedrich to fellow Alps native and contemporary artist Rudolf Stingel, but Godly did not look to their precedent, nor, he says, to any other, though he admits there are certain contemporary artists he admires.

Looking at the pictures, it’s impossible not to see in his viscous, visceral paint the faint echoes of Auerbach and Giacometti. Yet Godly harnesses the disconcerting power of impasto not to convey his irascible perspective but to reach towards the beauty and dignity of nature.

“When I started to paint again I didn’t need to think about what I wanted to paint – it was just so clear,” he explains, and it’s hard not to see the confidence and care with which he painted the mountains in his early years. There is a peace that comes when standing before the Alpine canvases, and an awe at their succinct expression. His palette is often restricted to just a few colours, and you realise anew the power of the mountains themselves, and when you take a few steps back there is something almost photo-realistic about them, despite the evident hand of the artist.

Credit: Conrad Jon Godly

In his process, Godly uses photographs only as a way to study light and fog, a type of visual notes. He paints exclusively from memory, working from small studies up to large canvases that reach two or three metres in size. He stands up close to the canvas and loads the brushes with thick paint, and then, he says, “I start to sculpt.”

“I work fast,” he continues. “Some paintings are finished in 30 minutes, others in three hours.” This immediacy, and the sculptural quality, are part of what makes his pictures so powerful: “I don’t make portraits of landscapes,” he explains, “I convey the mountains.”

Godly’s Japanese gallerist, Tokutaro Yamauchi of Shibunkaku, one of Japan’s oldest and best known galleries, says he was “astonished by Conrad’s ability to capture light and dark and adopt it onto the canvas with quick and minimal brushstrokes” when he first encountered his work in 2012.

“This use of oil paint resembles how the old masters of Japan applied ink to paper,” he continues. “I found a strong connection between Conrad’s painting and Japanese sansui [mountain-water, landscape] painting from the 15th century.”

Godly is pleased to have found acclaim in the Far East. He notes that he loves “not having to explain the paintings” because audiences have an intuitive understanding of what he is trying to do. As he prepares for his third solo show in Kyoto this summer, he has taken his pared-down palette – and the emphasis on simpler, though still dense brushwork – to a subject that is both similar and different to his first love: the brooding sea.

“The energies of the mountains and the sea have always been quite similar for me,” he says, and in his new pieces he has found a novel language to convey the smouldering waves: black-on-black paint. Working with textures and layers and reflections the paintings seem to glow – he is almost painting light itself. It is a remarkable evolution for Godly, and likely not to be his last.

Godly's painting Dunkel-24 (2011) adorns the cover of the Spring 2018 Centurion magazine

Visit conradjgodly.com