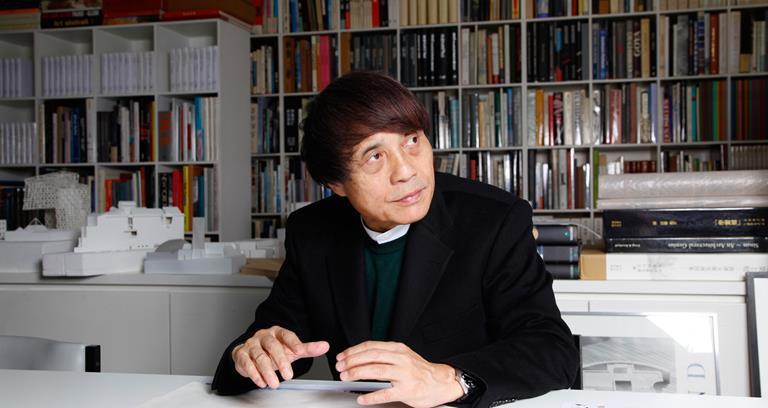

Talking with Tadao

In conversation with Pritzker Prize-winning architect Tadao Ando, on his design principles and vision for the future

Respected as one of the most influential practitioners in his field, Tadao Ando’s success, crowned by numerous accolades such as the Alvar Aalto Medal and the Pritzker Prize in 1995, is all the more precious, since a career in architecture almost passed him by.

Ando is famous among architecture buffs for having worked as a truck driver and even trained as a boxer in his early years. However, the lure of architecture would eventually prove irresistible for the young Ando, going on to take classes in drawing and interior design as well as visiting buildings by the likes of Frank Lloyd Wright before starting his own practice.

Now revered as an elder statesman, he remains as relevant and influential as ever – as evidenced in his latest project, the design of eco wellness retreat The Chedi Tomakomai – set to open in 2017.

We spoke with Ando to discover his true architectural values and vision for the future of architecture.

It is well-known that you took a different career path to that of most architects, having even trained as a boxer. When you look back, did you discover architecture or did architecture discover you?

The reason why I decided to be an architect is probably related to the living environment in my childhood, surrounded by scenes of manufacturing such as small local factories. On the other hand, was easy to access cities including Kyoto and Nara, where there are plenty of examples of outstanding traditional architecture. However, what motivated me to be an architect was actually my own will. As a means and occupation to be independent and live solitarily, I chose ‘architect’.

Which architect had the biggest influence on you in your twenties and why?

Since I started studying architecture by myself, I trained my sense of space by travelling abroad to visit actual pieces of architecture, instead of having any particular teachers. All around the world, in each place and time, there exist specific spaces which only their creator can have realised. I was honestly touched by this fact, and began thinking about the significance of the spaces and became absorbed into the world of architecture. For this reason it is difficult to pick anyone specifically. Nevertheless, if I had to choose it would be Le Corbusier. He fought with the society and defied cities all of his life. I found what architects should be, based on his extremely unrestricted creativity and challenging spirit.

What do you see as the primary goal of architecture?

It is to create new values beyond mere functions, which had not existed in the place before. In my opinion, that is not to add entirely new values but to draw out the potential of the place – ‘to create what does not exist there, by utilising what already exists there’.

Do you feel that one building in particular best represents the essence of your work?

Although I cannot point out a particular piece of my work as the best, I could say my early work: “Row House in Sumiyoshi” is the origin of my architectural career.

There must be various compromises involved in creating most buildings. As such, how do you view your finished projects?

It is natural that everything does not go on as previously scheduled, because we design spaces of dwelling for human beings who are full of contradiction. While an early image of architecture is being realised, numerous compromises are inevitably made out. However, I do not regard this as a negative process. I try to interpret those compromises as an opportunity to take other steps to improve the architecture. That is the most interesting – as well as the most difficult – process of architectural work. I believe that the deeper the conflict is, the stronger the existence of the architecture will be.

What recent projects have most inspired you or made you reconsider the way in which architecture can benefit society?

Recently, I have completed two green-planning projects in Osaka, where my office is located. The one is “Project of Urban Tree Building”, which has greened the wall of a symbolic tower in the office area in the city center. The other one is “The Wall of Hope Project”, which has converted part of an existing urban park into a green façade.

Both of them might not be regarded as architecture in the conventional sense, however in terms of the influence to the townscape and the contribution to public space of the city, those projects may have more significance than closed architecture within a given site. For the future, I envision a possibility of such borderless thought to architecture.