The Politics of Shared Spaces

In conversation with Nigerian painter Eniwaye Oluwaseyi about his politically charged exhibition at Accra’s Ada \ Contemporary gallery

Nigerian painter Eniwaye Oluwaseyi considers himself a critic and observer as much as an artist. Working in oil, charcoal and acrylic on canvas, Oluwaseyi’s latest exhibition, The Politics of Shared Spaces at Accra’s Ada \ Contemporary art gallery, examines some of the social, racial and political turmoil that’s erupted across Africa in recent years, shining a light on the #EndSARS movement, the ritualistic murders of Tanzania’s minority albino communities and the pressures of living in modern African society. His works are imbued with the struggles and experiences of the afflicted individuals; however, with vibrant colouration, he elevates these characters with what he calls a true “majesty”.

“Here in Africa, when we say someone is majestic, they dress in beautiful clothes and vibrant colours”, says Oluwaseyi. “When you see them, you see someone to look up to, someone of calibre.”

The Politics of Shared Spaces dissects what he calls African “blackness” amid societal unrest and ponders whether a harmony can be achieved. “How can we as a community coexist in shared personal and communal spaces, where everyone is able to work together and live in peace?”

Ahead of his exhibition at Ada \ Contemporary, Centurion Magazine spoke with the up-and-coming artist – whose works have recently been featured at Christie’s and UNIT London – about the series and delved into his insights about the burgeoning African art scene.

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi, A moment in time (family house), 2020

Centurion Magazine: The Politics of Shared Spaces showcases your first solo body of work. What themes did you explore and what are you hoping to communicate with this exhibition?

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi: I divided the works into three different series. The first one, I titled the ‘#EndSARS’ series. You know about the protests that happened in Nigeria – in my home country – in October? It’s just a little social commentary about the #EndSARS protests. Then, the next series is the ‘Albino’ series, on Sub-Saharan West Africa. This is a good one about a minority community, which has been ostracised and sometimes killed out of ignorance by the black majority. And now the third one is the ‘Family’ series.

The link between these three series is ‘Shared Spaces’. In architectural design, a shared space is a space you create without putting power over one another. It’s like creating a space in which, if you’re coming towards me or I’m coming towards you, we’re still at a certain distance, and we communicate. If you are going to take the left, then I’ll take the right, without conflict. Now, the community is our little shared space.

Are there any particular pieces that are, personally, especially resonant in the series?

Apart from the ‘Albino’ series, which is a very new body of work for me because, oftentimes, black artists have been cursed with this thought of painting black figures alone. They really mean a lot to me because, in future works, I’ll be going deeper into the coexistence of this minority and black majority.

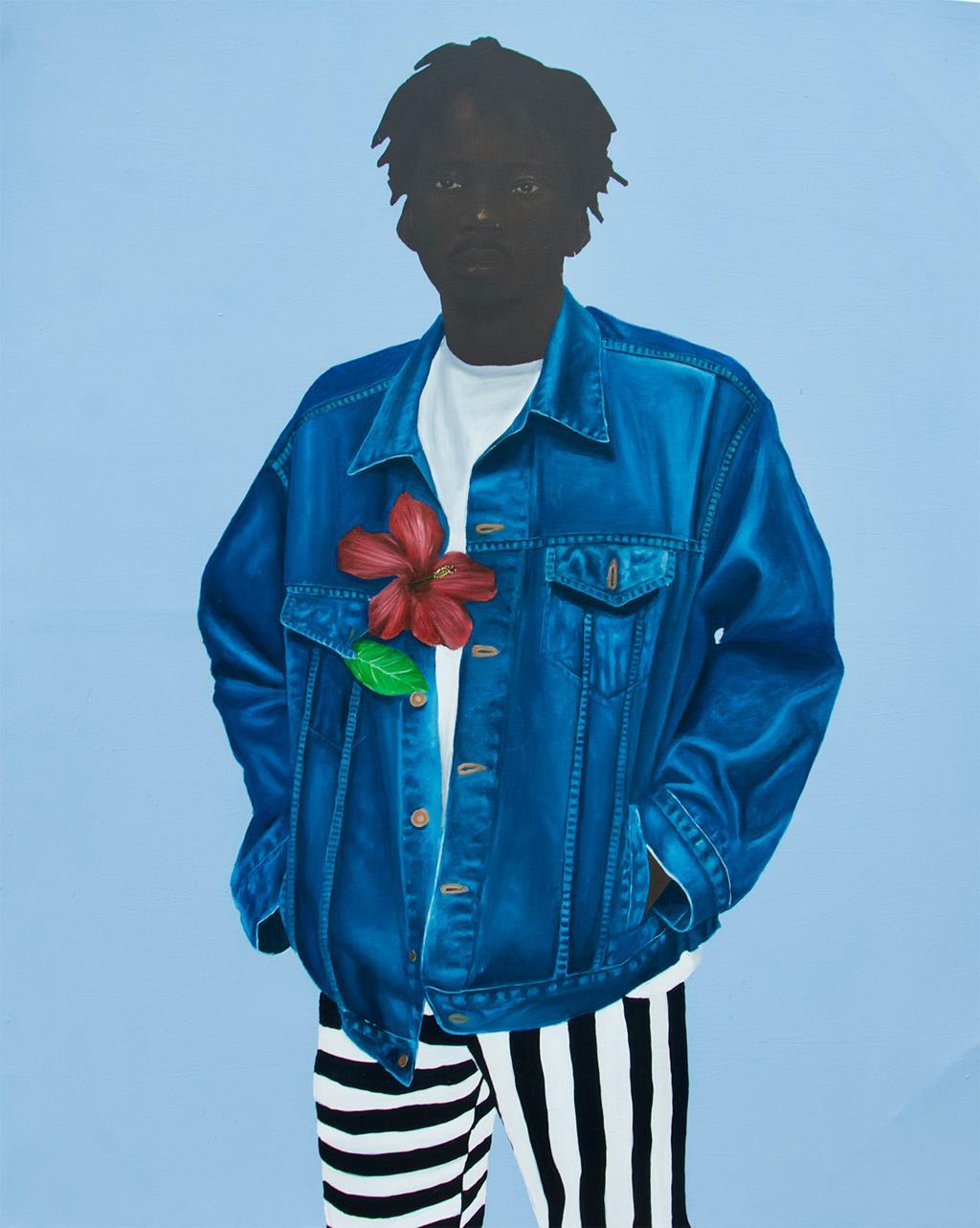

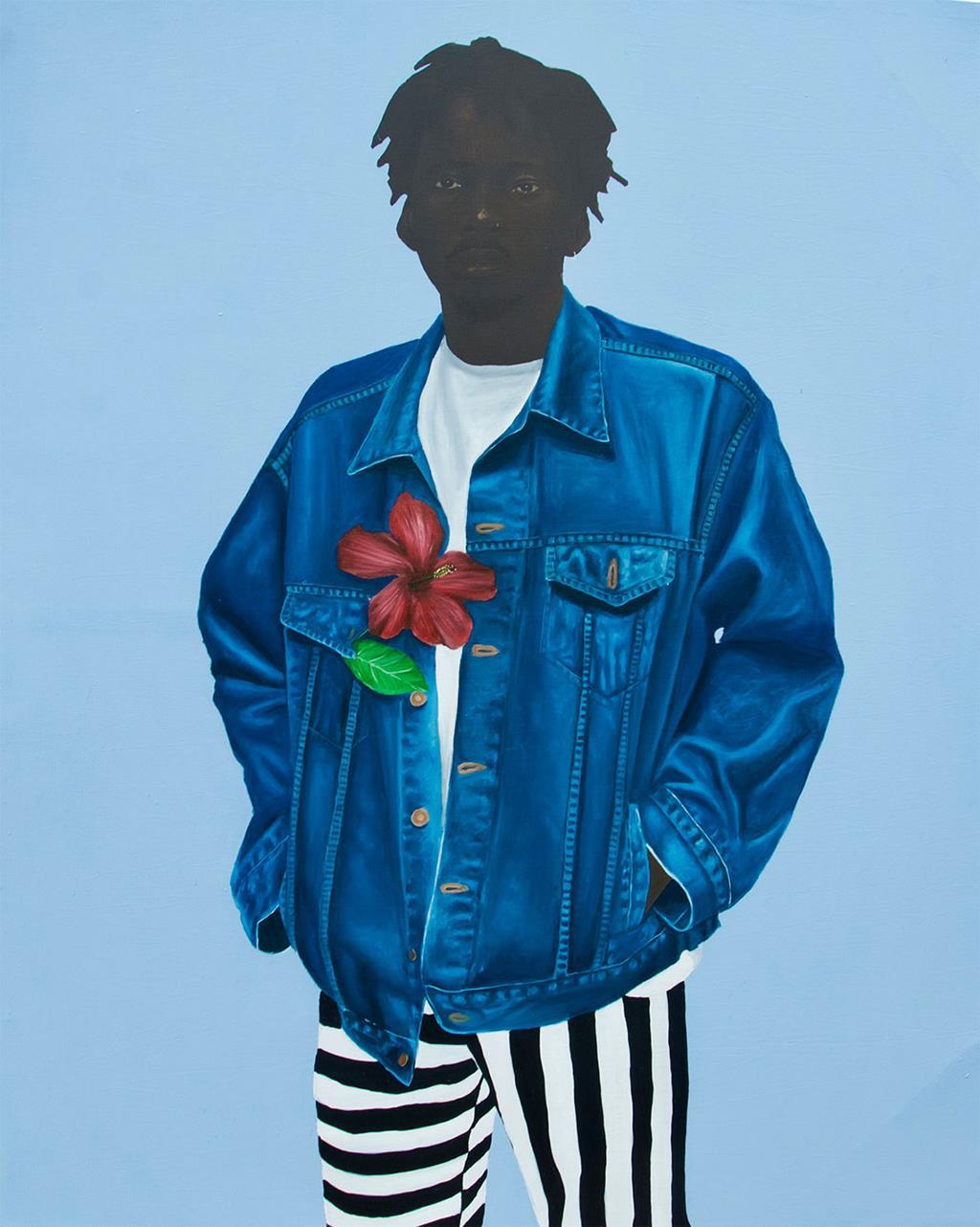

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi, Blue Jacket Lockdown, 2020

Apart from that, there’s this one painting titled “Blue Jacket Lockdown”. It’s one of my favourite pieces from the show. This is the very first painting I made during the pandemic lockdown. As an artist, when this happened in my studio, the only person with me was this old friend of mine – from a different background, different family, different experience growing up. We lived in this ‘little shared space’ for three months, just existing. And not a single conflict happened between us.

Now this made me realise if truly two people from different backgrounds, different experiences, all different, if they can coexist in my ‘little space’, if we are able to share this love and peace, then we should be able to return this back into the community. And if this love is within a community, then the majority of the black community, out of ignorance, would not be ostracising a minority. Or, if there’s love between the government and the citizens, I don’t see a reason why the government would order an army to shoot live rounds at unarmed citizens. Now, that’s the major turning point for my exhibition that the very first painting I made, it brought home all the ideas I had for the show.

Your paintings beautifully reflect humanity, particularly through your use of vibrant colours and unusual colour palettes. Could you talk a bit about your creative process?

I use colour as a total means of communication. I use vibrant colours for my subjects because, when you hear people talk about ‘people of colour’ ‘black people’, black people of colour, now this is an opportunity for me to just empathise with that statement. We are majestic. Down here in Africa, when we say someone is majestic, they dress in beautiful clothes and vibrant colours. When you see them, you see someone to look up to, someone of calibre.

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi, Boy from the other side, 2020

Also, if we look closely at my works, there’s this feeling off subtraction to the face where I emphasise mainly eyes. I call this ‘my little rule of subtraction’, where a person’s facial features are muted, neglected, just focused on the eyes. The eyes are the window to the soul. So, if you’re staring at my paintings, you’ll tend focus more on the eyes. You can feel what the subject is really feeling and try to understand the meaning of this painting on a different level.

It has to be a crazy time for you right now. You have this #EndSARS movement, COVID, lockdown politics, and then you have the entire Black Lives Matter movement that has exploded across the world, so it’s a momentous time in many ways. How is this influencing your work?

I consider myself a critical observer. Now, with everything going on, I think as a contemporary painter, it’s best as an artist to document my current times. If I’m able to capture this moment, then it can be history. At any point in history in years to come, these works can be referred to. Perhaps in the next ten years, one of the paintings from the #EndSARS series is put into subjection for discussion.

I see it as the job of an artist to document these times, and not just talk about something imaginary but talk about something real or something currently happening. That’s why most are subjects in my paintings.

How would you describe the evolution of the art scene in Nigeria – and even Africa – in recent years?

The first thing is I think social media has played a very huge role in bridging the gap. The world is now a small global village. This has really brought attention to young contemporary African artists.

Eniwaye Oluwaseyi, From the Other Side, 2020

And then, again, curators are now really focusing on ‘the black minority artist’. Even in the US, the black artist, they are not majorly represented by the big guns, the big galleries, and the change is now coming. With the use of social media and people’s attention to black artists, black figurative artists, black contemporary artists, black abstract artists, the change is coming. They’re works are being scene in bigger spaces, and it’s something good for black artists in Africa and even the diaspora.

Black curators and collectors are pushing for black artists to be heard. This is a new time for us and I’m glad we’re taking this opportunity to create great works. Honestly, I don’t see this ending any time soon. Not in this lifetime.

To close, what are your plans for the future?

Every artist will tell you they want to see their artworks going bigger, going international, bigger spaces, bigger galleries. I mean, as an artist, I want that, too. But, right now, I just want to paint the truth, the reality. I want to keep documenting this current time. I want to have paintings as a historical reference in times to come, paintings you’ll be able to see, resonate with. Bigger dreams for bigger works.

The Politics of Shared Spaces is currently on view at Ada \ Contemporary until 10 January 2021.