The Tables Are Turning

More and more of London’s restaurateurs and hoteliers are ripping up the hospitality rulebook. Fiona McCarthy goes behind the scenes at some of the city’s most enticing new venues.

From sipping Argentinian rainwater martinis overlooking views of Big Ben, the Shard and Hyde Park at The Emory’s rooftop bar to savouring fried-egg-topped carbonara at Peckham’s tiny Café Britaly to devouring moreish Comté gougères and chateaubriand at Maison François or sharing plates of dal, varuvel and bhatura down the pub at The Tamil Prince, the British capital’s hospitality scene is diverse, intriguing, even a little bonkers. Despite upended politics, fluctuating financial crises and ever-evolving Brexit, the city is hitting some of the world’s highest notes in terms of creativity, design, flavour and flair.

“What makes London such a magnet for restaurateurs, hoteliers, guests and talent alike – in what is probably the most competitive city worldwide – is that it is diverse and full of energy, life and new ideas,” enthuses Leonid Shutov, founder of Soho restaurant Bob Bob Ricard. Last year alone, according to data compiled by local restaurant website Hot Dinners, 253 restaurants launched in London, reaching almost pre-pandemic highs. At the same time, some of the biggest names in the global hotel scene have opened doors across the city, from Raffles London at The OWO in Whitehall; The Peninsula London at Hyde Park Corner; and the Park Hyatt London River Thames, the brand’s citywide debut near Vauxhall; soon, The Chancery Rosewood will open in the former US embassy in Grosvenor Square.

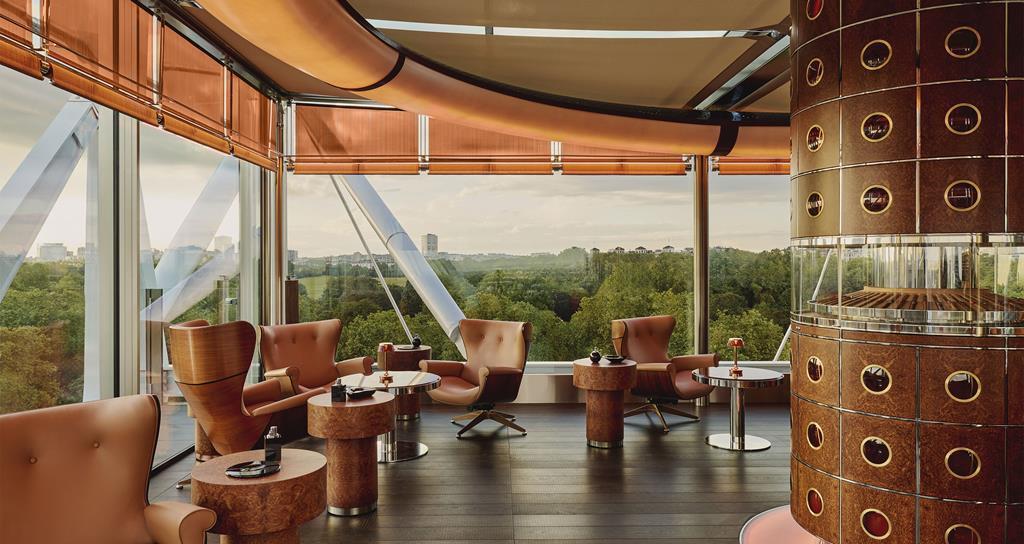

The most noteworthy openings, however, have been more left of centre. The Emory is at the top of London’s hotel game: one of the last projects to be designed by the late architect Richard Rogers, it offers just 61 suites across nine floors (with interiors by world-renowned designers such as André Fu, Pierre-Yves Rochon and Patricia Urquiola), all of which come complete with airport transfers (including helicopter), the use of a house car, a generous bar and an “Emory Assistant”.

Click "EXPAND" to see The Emory:

At Sloane – the result of a six-year collaboration between Cadogan Estates, Jean-Louis Costes (of Parisian Hôtel Costes fame) and French designer François-Joseph Graf – was born of the discreet and elegant but eclectic transformation of an 1889 edifice near Sloane Square into a six-storey, 30-guest-room hotel, with a top-floor restaurant and an intimate lower-ground-level bar. Whereas Noel Hayden’s Broadwick Soho is a tasteful take on the riotous eclecticism of a Soho drag queen’s wardrobe – candied shades of pink, red, green, wild florals and jungle creatures clashing with geometrics and stripes, Art Deco lighting and brass elephant-shaped minibars, patterned tiles and peppy veined marbles.

Click "EXPAND" to see At Sloane:

Click "EXPAND" to see Broadwick Soho:

Interestingly, while The Emory stands for the epitome of quiet luxury – its cobblestoned entrance obscured from the harried Knightsbridge thoroughfare – the acres of warm burl wood and amber glass of the ground-floor Jean-Georges Vongerichten restaurant ABC Kitchens make for an altogether more relaxed and accessible affair. With an emphasis on vibrant colour, zingy flavours and lots of vegetables – alongside British seafood – its well-priced dishes are the antithesis of the luxury-hotel fine-dining experience. “I’m bringing a more informal vibe, all about relaxing, socialising, sharing,” says Vongerichten, who also has a restaurant at The Connaught (and once upon a time in the 1990s, ran Vong at The Berkeley next door).

This sentiment echoes through the rise of the relaxed brasserie currently defining the buzzing London restaurant scene. Claridge’s Restaurant (previously home to New York chef Daniel Humm but now overseen in-house by culinary director Simon Attridge) has been given a stylish brasserie makeover by interior designer Bryan O’Sullivan and serves classic British dishes like eggs and (brioche) soldiers at breakfast, and black-truffle crumpets, fish pie and roast Norfolk Black chicken at lunch and dinner. Hot on the heels of launching new restaurants Socca in Mayfair and Brooklands in The Peninsula, the multiple Michelin-starred chef Claude Bosi and his wife Lucy opened Joséphine Bouchon in Chelsea, a laid-back Lyonnaise-inspired bistro which has been packed with locals and visitors ever since – an apt description, too, of The Dover, an Italian spot where the old-school approach includes reservations that can only be made by phone.

Click "EXPAND" to see Claridge's Restaurant:

Of course, no one does the grand café-style eatery better than Jeremy King. “To be open all day with a wide range of offers – and pricing it fairly – enables the restaurant to be something to many and allows the customer to make of it what they want,” says King, who over his 40-plus-year career has brought the likes of the celebrity-packed The Ivy and the elegant Viennese beauty of The Wolseley to London. Since his Corbin & King hospitality group, founded with longtime partner Chris Corbin, was bought out, King has opened The Park in Bayswater and breathed new life into Le Caprice (a restaurant the pair first ran in the 1980s), now renamed Arlington. “Restaurants should be catalysts for experience and intent,” muses King. “Historically, they have been the setting for innovation and creation in most cultural advances, whether art, music, literature, philosophy, politics and even revolution. I believe there needs to be a blend of people built from a belief in egalitarianism – all ages, all backgrounds, all beliefs.”

Click "EXPAND" to see The Park:

Click "EXPAND" to see Arlington:

This is certainly true in the proliferation of restaurants exploring more unusual global cuisines: Aji Akokomi’s restaurant Akoko and Adejoké (Joké) Bakare’s Chishuru, both in Fitzrovia, were awarded a Michelin star earlier this year for their innovative takes on traditional West African dishes. There has also been an exponential rise in popularity for Japanese omakase (with Endo at the Rotunda, Sachi, Mayha and Juno Omakase among the best); Kinkally has put Georgian dumplings on the map (stuffed with combinations of rabbit, foie gras, apple and fennel, or wagyu beef, peppercorn plum sauce and herb-infused Svanetian salt); while the collective of Kudu restaurants in Peckham brings South African flavours to the fore; and chef Chet Sharma (who has spent time in kitchens ranging from Mugaritz to The Ledbury) celebrates the recipes of his Indian grandmothers at BiBi. As King says, “In the absence of a strong food culture of our own, we took the cuisines of the world to heart. This has meant an open mind and limitless opportunity.”

“London remains the most exciting food destination in the world, and while this might cause uproar for those in Tokyo, New York, Lima, Paris or San Sebastián, the truth remains that it is largely due to the diversity of the scene that can be found here,” enthuses Ryan Chetiyawardana, the creative bartending genius behind Lyaness (the only bar in the world awarded three “Pins” by the Pinnacle Guide, the bar version of Michelin) and Seed Library in London. “There is an inherent mixing within London – the most expensive street in the world runs next to a council estate; everyone takes the Tube, rich and poor alike; the pub is a social meeting point for all walks of life,” he says. “But what has added to London’s food and drink prowess has been the willingness of the public to embrace new things, be it a fine-dining spot in Mayfair or a supper-club happening on the city’s outskirts.”

The food scene is also playing a pivotal role in attracting attention to new developments such as the Mandarin Oriental Mayfair, a 50-key hotel combined with 77 private residences in the heart of Mayfair, and The Whiteley London, a once-in-a-generation transformation of the former Whiteleys department store in Bayswater which includes 139 individually designed apartments; a Six Senses hotel, residences and spa; as well as three cinema screens, boutiques and a ground floor comprising dynamic new additions to the restaurant and cafe scene, including Israeli chef Meir Adoni’s forthcoming Catit.

Click "EXPAND" to see Mandarin Oriental Mayfair:

“Pavilion Road, Elizabeth Street, Marylebone High Street and now Queensway – where The Whiteley is located – are places people want to go for somewhere that’s fun, different, dynamic and buzzy, with shops and restaurants that don’t exist anywhere else,” says sales director Charles Leigh. “That’s really been our mantra for The Whiteley, to make sure that it’s full of interesting things for both the residents who live upstairs and the entire neighbourhood. Art galleries, artisan coffee shops, places with a younger vibe like Amsterdam-based Nela, which specialises in live-fire cooking. I mean, candidly, we’re not doing this just to be creative. It makes commercial sense as well.”

This commerce-meets-creativity vibe is common across the city: Bob Bob Ricard’s funky little sister Bébé Bob is evidence of Shutov’s belief that “life is too short to do boring stuff”, he laughs. “We see BBR being one of a kind and special – not a chain. Bébé Bob has allowed us to create a very different, much more relaxed environment while keeping the design every bit as glamorous and exciting with food that is elevated but, ultimately, something that most of us are happy to eat once a week, every week.”

Click "EXPAND" to see Bébé Bob:

London’s best restaurants are those with a personal touch, argues Oisín Rogers, co-founder of The Devonshire, a bustling pub in the heart of Soho which bursts at the seams the minute its doors open. Having previously been at The Guinea Grill, Rogers felt the West End needed “a big pub that wasn’t run by a big corporate”, he says. “A place where there is a bit of freedom, that feels honest and real, and the guy who runs it actually owns it.” With co-founders Charlie Carroll and chef Ashley Palmer-Watts, the trio is setting the bar high for a new way of eating, drinking and socialising in London.

Click "EXPAND" to see The Devonshire:

Alongside the likes of The Pelican and The Hero (which are both making a huge impact on the city with their pared-back, rustic interiors and concise menus) and The Pig’s Ear (adding to the stable of London restaurants infused with the goodness of the Gladwin family’s West Sussex farm and winery), The Devonshire is somewhere “people really enjoy being in a slightly chaotic and busy atmosphere with a very mixed, diverse and eclectic load of people, where you could end up standing beside somebody very interesting and having a great conversation. There aren’t many places designed for that to happen, and that’s what pubs are,” asserts Rogers. The food is amazing, too: its legendary steak sandwich might look effortless but the team “spent a year with different cuts of steak, different breads, different butters, different sauces, different presentations, different temperatures, different ways of cooking. That steak sandwich is probably iteration 45 of a long process. It doesn’t look like it, but when you do eat it, you know that something magical just happened.”

Photos credits: © Claridge’s, © The Park, © Kensington Leverne, © the Devonshire, Milo Brown