The Grape Crusaders

Independent champagne makers are producing fare to pique the interest of oenophiles everywhere

Last year’s record champagne exports offered a salient reminder that bubbly has lost none of its mystique for wine lovers the world over. The great champagne houses, led by prestigious cuvées like Moët & Chandon’s Dom Pérignon or Louis Roederer’s Cristal, have engendered over time an aura of exclusivity that still surrounds champagne to this day. But recently dozens of new coveted cuvées have emerged, and they’re not only coming from the cellars of Krug or Perrier-Jouët. Grower champagne is titillating the imagination of oenophiles like never before, as independent, avant-garde producers are redefining rarity in their image, with ultra-limited, single vineyard bottlings. “More and more growers are making authentic wines,” says the grower-producer Emmanuel Lassaigne. “It’s a return to our roots, to an era before mass production, with small cuvées that are definitely confidentiel, yet without a luxury label.”

Whatever the label, anyone who has savoured a bottle of champagne by Cédric Bouchard has glimpsed one of the wine world’s shooting stars. Bouchard’s micro cuvées – from foot-crushed grapes, fermented with natural yeasts, and disgorged without dosage – have left a seasoned critic like The Wine Advocate’s Antonio Galloni “literally shaking my head in awe”. Bouchard left behind a wine sales career in Paris to open his own champagne house in 2000, buying mini-plots around Celles-sur-Ource in Champagne’s southernmost Côte des Bar region to create Roses de Jeanne, the smallest wine property in the province. Bouchard brought a Burgundian notion of micro-terroirs along with a winemaking philosophy of “one parcel, one grape variety, one harvest”. His astonishing rosé champagne, Le Creux d’Enfer, originates from a .071ha parcel of pinot noir which yields an infinitesimal annual 300-500 bottles and which Galloni calls “one of the greatest champagnes ever made”.

The extolling of Côte des Bar wine is, to say the least, a recent phenomenon. Historically treated by wine authorities as a second-tier subregion, the majority of grapes are still sold off to big houses. Yet some always believed the area held exceptional terroirs: a former oenologist for Charles Heidsieck once christened the chardonnay slopes of Montgueux, with its pure chalk soil 15 million years older than that of Côte des Blancs, “the Montrachet of the Champagne country”. Emmanuel Lassaigne has strived to unlock this potential since taking over his father’s 4ha Montgueux vineyard in 1999. At every stage, Lassaigne patiently draws out the aromas of his terroir: harvests at optimum maturity; fermentations of several months in oak and steel; an elongated, low-temp prise de mousse phase conceived to create elegant, fine-grained bubbles. Cuvées like the barrel-fermented La Colline Inspirée, rich with notes of brioche, citrus and mineral elegance, have redefined Montgueux. Indeed, today Lassaigne is the toast of wine cognoscenti and hipsters alike in Paris, and his champagne appears on half the menus of the 100 best restaurants in the world.

For independent producers of Mareuil-sur-Aÿ in the Marne Valley, surrounded by the likes of Billecart-Salmon and Philipponnat, it’s never easy to escape your neighbours’ shadows. But when the children of two reputable local estates fall in love, their offspring are bound to be exceptional. Such is the case for the young couple Elodie and Fabrice Pouillon, with their curiously-named first-born, 2Xoz – a vintage cuvée of the finest old-growth parcels of pinot noir from their respective family estates. 2Xoz is at once a rupture with tradition and a rediscovery of the original champagne, whose bubbles developed from leftover residual sugars in the bottle. Elodie and Fabrice decided that instead of dosing their champagne with a sugar-based liqueur d’expédition, they would use the glucose- and fructose-rich juice of their own grape must. “2Xoz” thus refers to these two hexose-type simple sugars. The resulting 100% grape blanc de noirs is of uncommon poise and purity, with only 2,547 bottles made in 2004.

Champagne doesn’t have a reputation for breeding mavericks, yet perhaps no viticultural experiment was as gutsy as that which Jacques Beaufort undertook after suffering a series of mysterious allergic reactions in 1969. Bedridden for eight days and unable to swallow, Jacques finally realised the chemical vineyard treatments he was using were to blame. Less than two years later he entirely converted his 6.5 hectares in Ambonnay and Polisy to organic viticulture – the first of a handful of regional pioneers. Many said Champagne’s humid climate and deadly mildew made organic viticulture economic suicide – and indeed Jacques, like his son André soon after, suffered heavy losses at first. But as they developed new weapons in the form of plant and essential oil applications, grape quality took off. In 1997 the La revue du vin de France called Champagne André Beaufort “one of the most marvellous discoveries” of the decade, comparable only to Dom Pérignon. André Beaufort’s rise was underway. Today, Beaufort is world renowned, notably for his inimitable, zero-additive demi-sec cuvées, served, among other establishments, at René Redzepi’s Noma in Copenhagen.

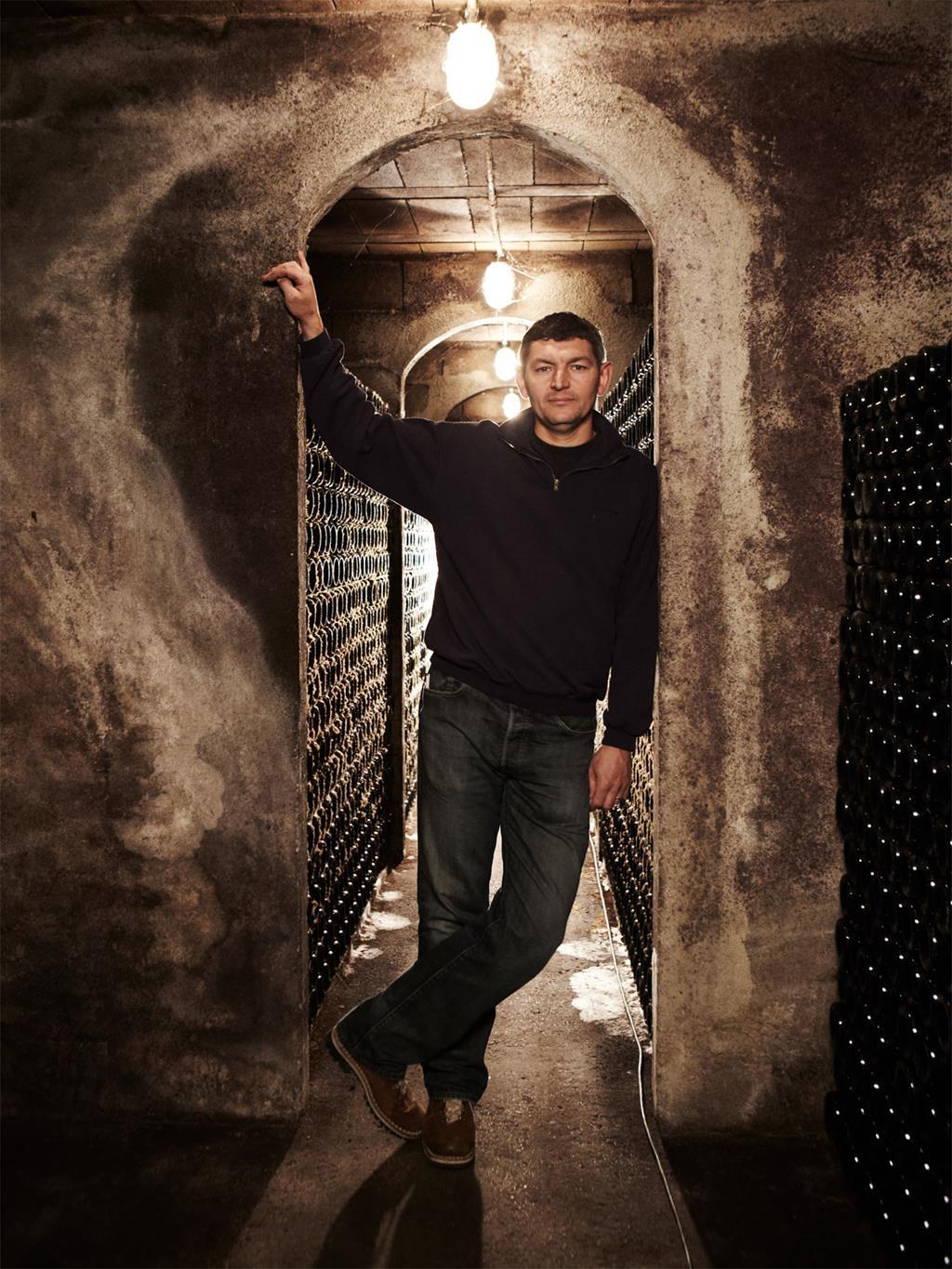

Beaufort blazed a trail to be followed, and indeed, one million bottles of organic champagne were produced in 2008, a number expected to double by 2014. Today, a tiny handful of growers are going further. Among them is Vincent Couche of Côte des Bar, who farms 13 hectares of pinot noir and chardonnay according to biodynamic agriculture. Seeking maximum grape maturity, he reinforces his vines with medicinal herbs, pulverised quartz powder and fermented manure composts, and may harvest two weeks later than his neighbours. His wine is unchaptalised, unfiltered and, as of last year, often vinified without sulfites – practices foreign to 99% of the region’s producers. “I don’t have shareholders or a bank pressuring me; I am 100% free to act as I choose,” he says. “But all my experiments have only one objective, and that’s excellence.” The marvellous vintage cuvée Sensation 1997 (5,000 bottles disgorged in April 2012) is revelatory of Couche’s considerable talent: opulent yet balanced by fresh acidity, redolent of buttered toast and candied fruit, and his zero-dosage cuvée is a sublime, crystalline example of this highly sought-after style.

This new generation’s peculiar mix of avant-garde thinking and traditionalism is epitomised by a grower like 29-year-old Alexandre Chartogne. Chartogne-Taillet, located in the northern Montagne de Reims, has been in his family since 1683. Chartogne spurns chemical fertilisers and herbicides, and has studied centuries of vineyard journals his ancestors kept to find solutions to daily problems: he lets sheep roam his vineyards to keep cover crops in check, prefers horses to tractors, which compact the soil, and maintains a parcel of rare, ungrafted pinot meunier using an ancient vinetraining method called provignage. Yet Chartogne isn’t backwards-looking. Like his mentor Anselme Selosse – who first brought Burgundy winemaking techniques to Champagne – Chartogne vinifies in oak his rich, highly-coveted micro cuvée, Les Barres (500-2,000 bottles annually). Yet a delicate wine like his Beaux Sens, a 1,000-3,000-bottle single-parcel cuvée of pinot meunier, Chartogne vinifies in space-age-looking egg-shaped concrete vats. He draws on the expertise of France’s most esteemed soil microbiologists, Claude and Lydia Bourguignon, to tend to each vineyard parcel as unique individuals whose personalities he seeks to channel into wine. And that means putting his champagne’s integrity ahead of his clientele and their unquenchable thirst – trying to satisfy demand only leads to the kind of artificial intervention that effaces terroir, he says. “I find it more interesting to taste the differences between soils, than the difference between oenologists. What I appreciate about wine is discovering what nature gives us.” What it gives Chartogne is magnificent – and maddeningly meagre in quantity. But that’s also what makes such cuvées so compellingly covetable.