An Unlikely Indulgence

From deep-sea divers to award-laden chefs, a look at how the beguiling sea urchin has climbed the culinary ladder

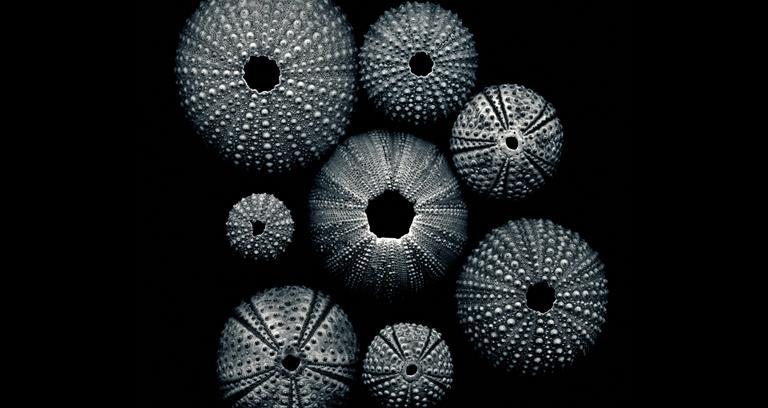

Perhaps it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the most disagreeable-looking maritime delicacies are also some of the most expensive. After all, the armoured langoustine and pincer-wielding lobster are no charmers, but the sea urchin stands alone in its power to menace: resembling nothing so much as a multi-hued subterranean hedgehog, its profusion of defensive spikes makes for a decidedly hostile first impression. And because most of the creature’s energy is taken up with its defences, the edible portion inside the shell is only about 10-15% of its weight, which means its flesh starts at an astonishing €200 per kilo.

No-one knows who first penetrated the sea urchin’s spikes, though they do appear in the earliest recipe books of Europe, including that of Apicius, who wrote ancient Rome’s definitive cooking tract. He includes four dishes that feature them and also tells the story of an ignorant Spartan who eats a whole one – external spikes and all – before declaring he would never try one again. And while the actual taste of the raw flesh, an intense maritime flavour of iodine and brine, hasn’t changed in millennia, its application certainly has with chefs nowadays, who are using it as a deeply decadent flavouring in dishes ranging from pasta to omelettes.

Sea urchins are some of the ocean’s most perishable produce and most experts believe they must be eaten within just 36 hours of harvesting. This means that elaborate arrangements are taken in order to get them to the plate in time. Olivomare, the Sicilian restaurant in London’s fashionable Belgravia, uses sea urchins from Sardinia in two dishes, courtesy of special couriers at Heathrow who pick them up immediately after they clear customs and rush them to the restaurant.

One person responsible for keeping the standards at the very highest level is a Scottish diver who lives within the Arctic Circle in Norway. Roderick Sloan, 41, has spent the past decade diving for sea urchins, first around Bodo and then even farther north near Nordskot. On a good day he can harvest 200 kilograms from a depth of between six and 15 metres. He only dives for them between September and February and doesn’t revisit a site for five years in order to give them an opportunity to regenerate. He has clients across Europe, including René Redzepi at Noma in Copenhagen, where he can ship them within eight hours.

“When I came to Norway to do this, everyone laughed at me,” Sloan says, “but I stuck at it. For me, it has to be the challenge and also the pleasure of diving – it is the quietest place on the planet.” However elegiac he is about the landscape, he doesn’t have any idea why the Norwegian sea urchins he plies are so delectable: “It must be the northern lights or something equally magical.”

A number of other leading three-Michelin-star chefs in Europe use Mediterranean species, including Gerald Passadet at Le Petit Nice in Marseille and Massimo Bottura at Osteria Francescana, near Modena, who uses specimens from the Adriatic Sea near Puglia. “Currently we have two plates with them on our winter menu,” says Bottura, “‘Salty Dog’ and ‘Risotto falling between the earth and the sea’.”

What is perhaps most surprising about sea urchins is that they have only become well known in culinary circles in the past four decades, and this happened, initially, because they were considered a pest. Sea urchins are vegetarian, often feasting on different varieties of kelp and seaweed. Because these plants were a major crop, the US government began a programme in 1971 to encourage the harvesting and consumption of sea urchins, which has now become far more important financially than the kelp industry.

The leading proponent of sea urchins nowadays in the US is Japanese chef Sotohiro Kosugi, whose New York City restaurant Soto is both unassumingly austere and highly reputed. He purchases most of his crop from California, where the species are particularly large and succulent. “I love the ones from Santa Barbara and Santa Catalina Island because they consume giant kelp, which has a positive effect on their flavour. The ones from Maine consume different sea vegetables, which affects the taste.” Kosugi uses sea urchin roe in a variety of dishes, including with squid and quail eggs and as a mousse with lobster, in addition to adding it into slices of sushi.

Other chefs use sea urchins in still different combinations: the recently opened Agape Substance in Paris has a dish which combines sea urchin in its shell with coffee, and Sydneysider Mark Best serves sea urchin with mandarin and green tea in a cocktail glass at his superb eatery Marque.

With such an extraordinary range of permutations making them so versatile and appealing to chefs around the world, it almost makes you reconsider whether the creature’s exterior is so threatening after all. One thing is certain: we can be glad their defences work against most sea creatures, leaving their hidden bounty for us to enjoy.