Future Art

From virtual reality and artificial intelligence to infrared imaging, tech advances are transforming both the everyday world of the art market as well as the possibilities of artistic creation

In 2014 artist Marina Abramović banned mobile phones, cameras and watches from her exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in London. It was easy to understand: she wanted visitors to focus on the art itself and not distract from it or record the moment. So it was something of a surprise earlier this year to see Abramović’s first virtual reality artwork, Rising, at Art Basel Hong Kong. A gripping experience in person, it’s soon to be available round the globe to anyone with a smartphone, viewable with a simple cardboard VR headset.

Abramović’s quick assimilation of the new tech has been mirrored across the art world. Suddenly new mediums are everywhere, and art looks more chaotic, optimistic and democratic than it has for many years. Artists are making the most widespread use of the innovations, pushing boundaries that once seemed impossible to cross. But gallerists and auction houses, too, are tentatively venturing into the new landscape, finding new ways to present works and inform clients. And increasingly lawyers and scientists intent on solving some of the industry’s most intractable problems – price transparency and forgery – are using technological solutions with remarkable success. The death of realism, the death of painting, the death even of conceptual art: all have been mooted over the past century – and now increasingly eyes are turning away from the past and toward the bright new dawn of possibilities, even if no one yet knows quite what the innovations will bring.

Marina Abramović, still from Rising, 2017, courtesy of Acute Art

Anish Kapoor, Jeff Koons and Olafur Eliasson have joined Abramović with recent VR debuts, all established artists who are keen to explore the new space – and who all worked with the team at London-based Acute Art to realise their vision. Less than two years old, the firm is fast rising on the global scene – at year’s end it will welcome new director Daniel Birnbaum, formerly of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm and a past director of the Venice Biennale – but it is hardly alone, being one of a bevy of new companies that are producing new VR pieces round the globe.

Some of the art can only be seen in special museum exhibitions – there have been recent displays at, among other venues, MoMA, Robben Island Museum in Cape Town and BOZAR – and some galleries, like the Zabludowicz Collection, have come to specialise in it, but largely at this point the works are almost all available for free on various smartphone apps and, in some cases, for privately owned Oculus Rift headsets.

Anish Kapoor Courtesy of Anish Kapoor and Acute Art

Anish Kapoor, stills from Into Yourself, Fall, 2018 Courtesy of Anish Kapoor and Acute Art

Anish Kapoor, stills from Into Yourself, Fall, 2018 Courtesy of Anish Kapoor and Acute Art

Anish Kapoor, stills from Into Yourself, Fall, 2018 Courtesy of Anish Kapoor and Acute Art

Elsewhere in the digital sphere, Instagram-based artists are furthering the discourse on ownership, the aura of the object and the possibilities of images. Argentinian Amalia Ulman has worked in several mediums, but her Instagram photos on her account @amaliaulman, starting from 2014, have earned her worldwide acclaim. Another Insta-artist, Paperboyo, works with cut paper to create surreal dioramas and was part of a recent LG launch for the LG SIGNATURE OLED TV W, which has a screen just 2.57mm thin and utilises groundbreaking LG OLED pixel technology to create a picture of astonishing depth, contrast and clarity offering its own possibilities for display of digital works of art.

The ultra-thin LG SIGNATURE OLED TV W

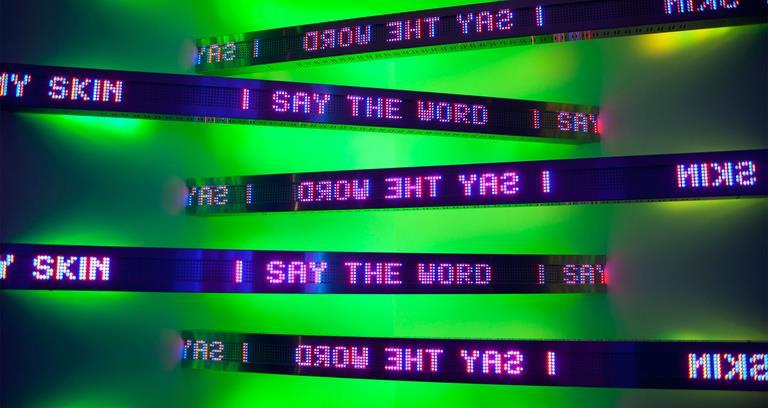

And when it comes to text-based digitalisation, Jenny Holzer, whose flashing LED slogans can be found in every major global contemporary art museum, is having a revitalisation of appreciation, her works so clearly foreshadowing the epigrammatic potential of Twitter, demonstrating just how powerful and how simultaneously impotent a few dozen characters can be.

On the commercial front, the digital works pose a problem that remains entirely unsolved: who can or should own the works? When they are so easily transferable – the matter of copying code from one device to another – there seems little reason to keep them sequestered. But then how do artists make money?

MONUMENT, 2008 © 2008 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY Photo: Vassilij Gureev

FLOOR, 2015 © 2015 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY Photo: Ken Adlard

Jenny Holzer Photo: Nanda Lanfranco

French art collective Obvious is turning that problem on its head by getting the machines to make the art themselves. In October, Christie’s New York will sell a print on canvas that was created entirely by artificial intelligence, Portrait of Edmond de Belamy. The algorithm, fed a set of 15,000 portraits from the past centuries, taught itself what a portrait was and “painted” the picture of a man who does not exist.

The sale of the AI portrait is a risk for the auction house – subverting our expectations of an artist consciously making choices – but Christie’s and other auction houses and galleries are much more at home with another technology that is radically changing how we buy art. Online galleries – no different in principle from any other online shops – are responsible for an increasing percentage of art sales globally. According to the industry-leading Hiscox Online Art Trade Report, online sales in 2017 reached $4.22 billion, up 12% from the previous year.

Portrait of Edmond de Bellamy, Obvious

But gallerists and auctioneers are not only seeking sales, they are often tasked – and indeed, for many, are primarily tasked – with educating current and future clients about the art. And online resources – from blogs to videos to emails – have become essential resources, with some platforms, such as Artsy, spend a significant budget exclusively on education.

Part of the appeal (or drawback, depending on your perspective) to online sales is the price transparency. In the mid-20th century it was possible for the Nahmad brothers to buy Picassos and other works from Daniel Kahnweiler in Paris and sell them in Italy a few weeks later at a significant mark-up, spearheading their art empire. Nowadays such dealing would be impossible: travel and art fairs make global connections easier, and price transparency on the internet, especially at auctions, means the going rates for an artist are easy enough to tabulate, and websites such as Artprice and Artnet do so, to the great benefit of collectors.

Similarly, scientists employed by gallerists and collectors are using new technologies to thwart forgers as never before. Whether it is chemical analysis on a scale heretofore impossible or infrared scans of a canvas to literally see what is underneath, the developments have been astonishing – and have brought down, among others, perhaps the 20th century’s greatest forger, Wolfgang Beltracchi.

There is a real question about what authenticity will mean in coming years

With virtual reality and augmented reality and works created by artificial intelligence, however, there is a real question about what authenticity will mean in coming years. Can you forge a VR or Instagram work of art that is freely distributed? Will anyone want to own them? Technology has up to now played only a tangential role in the art world, and there have been similar rumblings about previous innovations, from photography to video, that have added to the richness of artistic possibilities but have not quite proved revolutionary. Still, the excitement is palpable among those engaged with the new mediums – whether young digital natives or the older generations discovering their power – and it’s hard not to hope that the new technologies will lead to new engagement with art and new, powerful works.

To read more about the LG SIGNATURE OLED TV W, visit our product showcase. Or head to LGSIGNATURE.com to find out more.